Skiing Argentina’s Patagonia pow

Words Ross Hewitt

Photos Ross Hewitt | Michelle Blaydon

At 37,000 feet above the Argentinian plain, the unbroken featureless brown moonscape stretched for as far as the eye could see. Dead straight roads spanned for tens of miles. It seemed an unlikely place to go skiing.

Finally excitement levels rose as out to the west I got my first glimpse of the fabled Andes mountain range that forms the backbone of South America. As I stepped onto the tarmac at Bariloche, a pretty lake-side town in Argentina’s Patagonia region, I instantly recognised the mountainous silhouette of the Frey backcountry area from studying Frederic Lena’s Handbook of Ski Mountaineering in the Andes.

A taxi dropped my partner, Michelle, and I at one of the numerous hostels in the centre of Bariloche. With its wooden-clad chalets, boutique chocolate shops and pretty squares, Bariloche felt like some quaint Alpine town as we wondered around it that evening in search of a restaurant. We settled on Cervecería Manush, a brewpub serving up tasty pizza and home-brewed beers.

The next morning we took the iconic yellow US school bus to Cerro Catedral ski resort. The 25-minute journey out (which included an emergency stop outside a bar so the bus driver could get hot water for his morning cup of Mate infusion), took us along the scenic tree-lined shores of Nahuel Huapi Lake and up into the foothills of the Andes.

At Cerro Catedral the view stretched from cobalt blue lakes ringed by woodlands up into the snow-crowned peaks that hold promise of good adventures. Spread across 3,000 acres, Cerro Catedral has the largest lift-accessed ski terrain in South America, around half of which is off-piste terrain. The tree skiing is legendary and if you venture beyond the marked ski area there are some interesting backcountry routes – which is precisely what we had come for.

We skied down a little from the top of the Del Bosque chairlift and then switched into touring mode. We skinned skier’s right and around the ridge leaving the ski resort boundary. There we found a lovely 200m-high back bowl under the peak Diente de Caballo that held untracked powder between the golden granite spires that attract so many rock climbers to this region in summer. After a few runs in this bowl with short skins back up, my jet-lagged mind and body started to feel alive again, stimulated with the possibilities I could see around me.

Back at the hostel we made plans to visit the Frey refuge. The Frey is Cerro Catedral’s iconic backcountry area – it featured in an episode of Skier’s Journey by the talented filmmaker Jordan Manley. The refuge, located at the foot of Frey peak, promises the backcountry skier good times skiing among the Patagonian spires during the day, with warm hospitality, pizza and Malbec around the stove come nightfall.

The next morning we took the Del Bosque chairlift once again, and skinned up the bowl from the previous day. This time veered we left to the ridge overlooking the Arroyo Van Titter valley and found one of numerous couloirs that would take us to the valley floor. The shady line contained sublime skiing with deep cold blower, and we whooped and hollered as one turn followed another to the valley floor. There we put on skins for the climb to the Frey refuge.

Arriving at lunchtime we were rewarded with that classic view beyond the refuge of the snow-covered Tonchek lake encircled by sky-piercing granite spires. The temperatures were still low that afternoon, so we headed straight out, skiing across the frozen lake and then boot-packing up among the spires to ski a couple of lush lines in powder. That night there was an international gathering of skiers and boarders in the hut and a great atmosphere as we swapped tales and jokes around the stove and feasted on homemade pizza.

Susceptible to wind events, weather windows are often short in Patagonia. After another day of skiing from the Frey hut, we decided to return to Bariloche rather than wait out a two-day storm at the refuge. That night we had the pleasure of dining with local mountain guide Jorge Kozulj and pro skier Eric ‘Hoji’ Hjorleifson for a wonderful traditional meal of Lomo steak and Malbec at the Alto El Fuego Parilla.

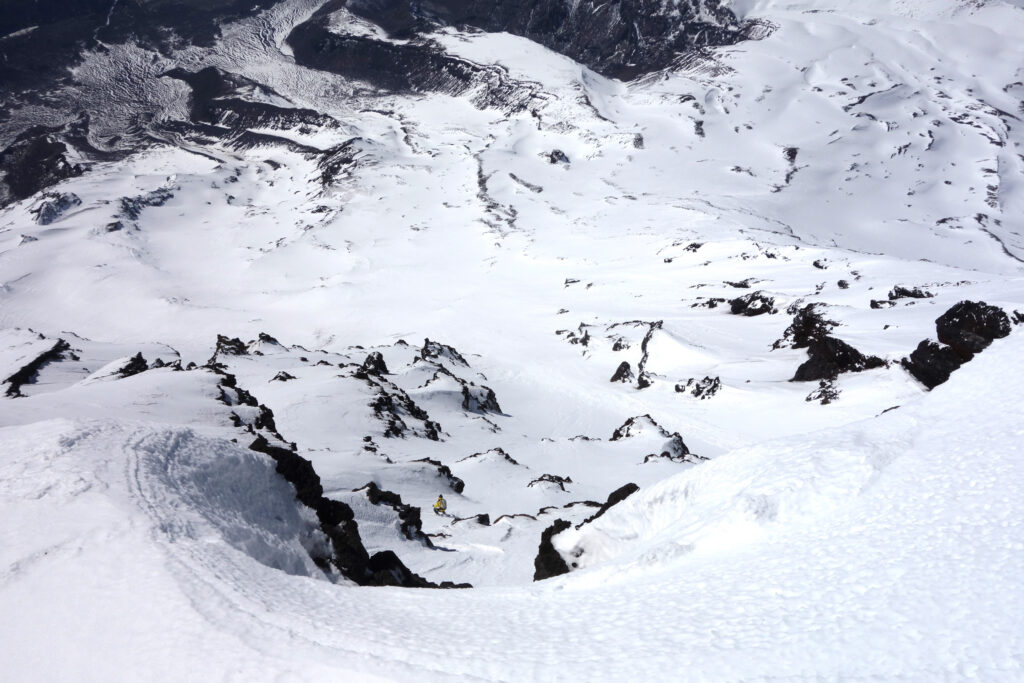

I’d never been on a volcano, let alone skied down one, but I was about to do both. We had driven four hours’ north to the Chilean border where the ice-clad Lanín volcano is situated. At 3,776m, it is the highest volcano in the Lake District and one of the tallest in Patagonia. Our interest lay in the 1,000m north-east couloir right off the summit, similar to the Cosmiques Couloir in Chamonix, albeit without the Aiguille Du Midi cable car running to the top and without the acclimatisation the Alps offer.

Starting at the 1,200m road pass we hiked and ski toured up 1,600m to an old military bivouac RIM26 that offered a welcome shelter from the elements. There we met a couple fellow skiers: pro photographer Adam Clark (long-time contributor to Fall-Line) and pro skier Brodie Leven. Both were looking somewhat forlorn. Their stove wouldn’t work, which meant they had no way to melt snow for drinking water or prepare their freeze-dried dinner. Skiing the next day without having had any fluids or food for 24 hours would be rough to say the least, so we were happy to share our stove (weirdly, their gas cylinder worked in our stove, and ours in theirs!).

In the morning we watched the fireball sun rise over the horizon and light gradually reveal the spectacular landscape of volcanos and lakes. We got underway quickly, eager to get the blood moving and warm the body.

Initially we made good progress skinning, but as we moved higher there was ever-increasing amounts of rime on the surface and we switched to crampons, weaving a path between these petrified wind-formed rime structures to the summit. We were gifted with a clear windless day, so upon reaching the summit the four of us took the time to soak in the views over this incredible landscape.

Here was our dream line filled in with compact powder that the wind had carried over the summit

We were pretty certain the ski down was going to be ultra scratchy what with all the rime, but we decided it was still worth looking into the north-east couloir on the off chance that there was good snow hidden in there, as the prevailing weather was from the south-west.

As I closed my boot buckle ready for the descent, I heard a crack and looked in disbelief at the buckle that had come off in my hand. The buckle had dual functionality, both doing up the cuff and locking it in ski mode. I was gutted – our biggest peak on the trip and I was going to have to ski it with one boot in walk mode! There was nothing I could do apart from use my ski strap to cinch the cuff tight. It was a case of making the most out of a poor situation, but I was confident I could still ski the line by maintaining forward pressure on my boot at all times.

We carefully moved down the ridge that separated the normal route and the couloir with edges struggling to bite into the icy rimed surface. It was more exposed than I guessed it would be, but as we got clear of the summit cornice our position gained full view of the couloir. We couldn’t believe it – in stark contrast to the poor conditions on the mountains, here was our dream line filled in with compact powder that the wind had carried over the summit.

A few careful moves got us into the couloir where we enjoyed the best run of the trip on great snow. Patagonian powder at its best.

As I joined the others at the base of the couloir, everyone wore massive smiles. Between the faulty stove and high-altitude petrified rime structures, this was truly an unexpected and exceptional gift. We skied the final 1,500m down to the valley floor and walked out leaving behind the black volcanic rock and entering the new forest, all the time with Lanin looming overhead.

The next day, back in the air 37,000 feet above the Argentinian plain, I would peer through the airplane window and try to spot Lanin, a final look at this mighty peak that delivered a descent that I would remember long after my return home.

Ross Hewitt is an IFMGA mountain guide. To learn about the South America ski adventures he guides, and to book him for your next adventure, click here.

* Ross is sponsored by Black Crows Skis, PLUM bindings, Scarpa, Petzl, Julbo Eyewear, Arva, Snowcountry EU, DB Journey, and Sapaudia Brewing Co.