A day in the life of Chamonix-based skier and photographer Ben Tibbetts

At 3am, I regularly eat dry bread, helped down with one tiny square of butter and one of apricot jam, in a cold dining room on the shoulder of a mountain. If I’m in a Swiss hut that’s probably the limit. If it’s a French one I might get a piece of fruit as well, if I’m lucky.

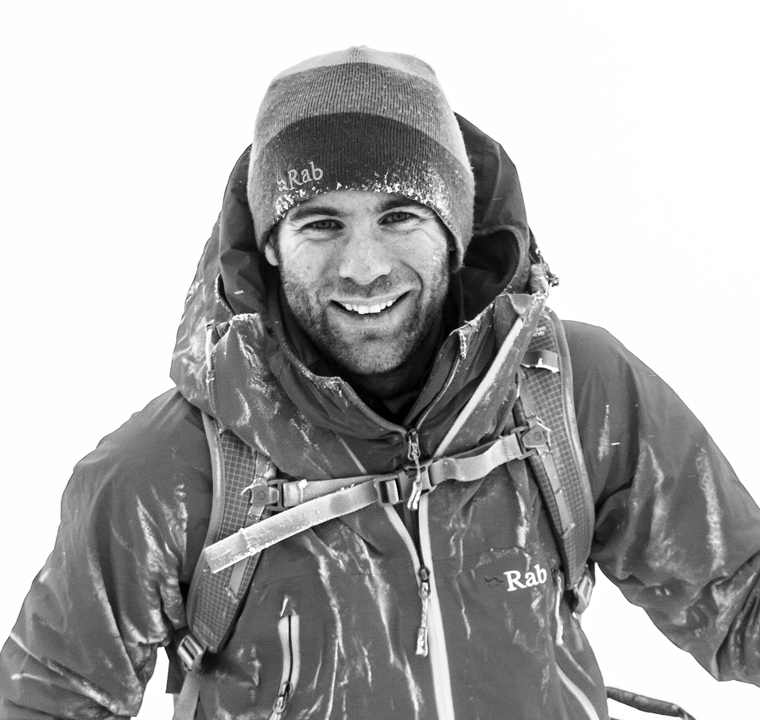

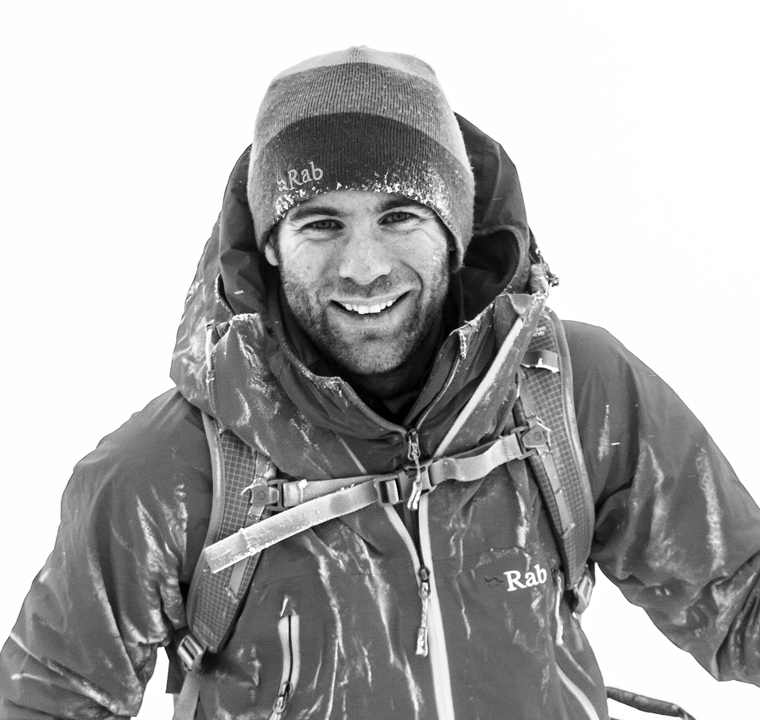

A multi-talented dude |Tom Grant

Before breakfast, I’ll have been outside to feel the temperature of the air, see how clear the sky is and prod some snow to check how good the re-freeze is.

My day is all about conditions and timing. I usually try to reach the base of climbing technicalities along with the first bits of light. On the way up, I’ll only pause at dawn to bag the prime shots of the day. The aim is to hit optimal snow conditions on the way down and, most importantly, spend as little time on the mountain as possible. Keeping moving is one of the hallmarks of alpine safety.

First things first: after breakfast I’ll stick my fingers in my eyes to put my contacts in, probably getting grit in there as well as there’s no running water. I’ll get my boots on while chivvying my client along, trying to get them enthused about being up at 3am for a two-hour walk up a moraine or glacier.

Then the world’s reduced to a little pool of headlamp. I tend to feel nauseous for the first 30 minutes of the day, so I start at a slow, plodding pace and build up until it’s time to stop and get the helmet, crampons and rope on; perhaps when we reach a steep snowfield.

From this point I need to be switched on, watching my feet – their movement and crampon placements – and fully engaged.

At the base of the route I’ll try to find somewhere to stand without fearing for my life and eat a sandwich while watching the first inklings of daybreak. I’ll probably get the camera out here, and take some photos of my client gearing up.

Ben was stoked to get this shot of Tom Grant in a particularly tight spot in the North Couloir of the Col Du Plan | Ben Tibbetts

Over the past couple of years I’ve been trying to find, climb, where possible ski down, and photograph the best routes on all the major 4000m summits in the Alps. I live in Chamonix and it makes for a great base. I’m writing a series of articles about these routes, which are published in three countries: on British website UKClimbing.com, in American magazine Rock + Ice, and in French magazine Montagnes, translated by my girlfriend. When I’ve finished the project I’ll put it all together into a book.

I grew up in the Welsh borderlands, and first got into skiing and climbing in Edinburgh, where I studied Fine Art at university for seven years. My art was always landscape-based, but it gradually became more conceptual. The ideas were more important than the aesthetics.

I applied for a post-graduate art course in Geneva because the tuition fees were much lower than in the UK and the Alps were nearby. I assumed the course was taught in English, as the university website and the interview were. It wasn’t, and I didn’t speak a word of French. I learned rapidly!

When I finished my degree I wasn’t sure whether to become an artist, or follow my love of skiing and become a mountain guide; so I moved to the Antarctic. Working for the British Antarctic Survey as a field guide was a bit regimented, and that pushed me to go for my guides badge. I wanted the freedom to work in these places with my own clients.

On my art course I’d studied photography, but was pursuing conceptual black and white images using heavy large format camera equipment that took one 5x4in negative at a time. I bought my first digital SLR before going to Antarctica,

and started taking traditional documentary-style images.

I got back from Antarctica with savings (as there’s nothing to buy there!), and that supported me through completing the guides scheme in Chamonix. I started selling photographs then, too, and things just progressed from there.

My guiding, photography and editorial work go well together. Through the articles I’ve developed a name for ticking off the best routes up and down 4000m peaks, so I get lots of clients who want to do them with me. I take about a third of my stock photography while guiding, which means clients can have good photos of their day out, too.

I usually have the camera on my waist belt right from the hut. If not, then it goes on there at the base of the technicalities. Then it’s into the climbing. Most of the guiding I do involves moving together on a long rope with me placing gear, and perhaps short-roping clients up scrambly sections. And so it goes, moving up slowly and carefully. Once it’s light enough that I can turn the head torch off, the day starts to feel more acceptable, and I come back into the land of the living.

Around daybreak I’m excited as I know I’m about to get a load of photos. If whoever I’m with is up for it, I spend half an hour trying to find an aesthetic spot – maybe an exposed situation or a pretty good view – and going up and down it a few times.

Most guides would consider this absolutely nuts; they just want to get down again quickly and safely and have their coffee, but I enjoy working a short passage, trying to get that key shot. The first half hour of sunlight is such a strong, colourful and atmospheric time that good shots often come thick and fast.

I almost always carry a long telephoto lens, which weighs just over a kilo and is only useful for sunrise; after that the light becomes too harsh and blue-toned. In that first half hour, though, there’s so much contrast and colour it’s worth carrying the lens for two or three days just to use it for half an hour.

After sunrise I’ll only stop on the way to the summit if there’s an obvious shot to be taken. I’ll usually see these coming and try to approach the scene in a way that allows me to get the best possible shot of my partner in one take. I know when I’ve got a good one, but on editing a day’s photos back home there are always many happy surprises, and often these turn out to be more special than the obvious shots.

For example, any of the routes on the North Face of the Aiguille du Midi are going to be memorable experiences, but because of the steepness of the terrain it isn’t a very easy place to shoot. So I was pretty stoked to get a particular shot of Tom Grant that gives a sense of it all (see above). The ski marks are each of Tom’s jump turns, so that should give an idea of the angle of the tight slot couloir!

I try to keep the pace up when on a high peak, as you never know what the weather will do. When I did the South Face of Ober Gabelhorn, one of the big peaks that surround Zermatt, the weather forecast, even the one I read that morning, was for an absolutely clear and windless day. But it started raining when we were at 4000m, and thundering and lightning higher up when we were in a place we couldn’t retreat from. These things do happen, so it’s important not to expose yourself for longer than necessary.

Another Ben classic: Liz Smart on the Dent d’Emaney in Switzerland | Ben Tibbetts

If skiing down, we’ll usually scramble back down from the summit to wherever we stashed our skis. You can’t ski off all the 4000ers, but a few good ones that you can are the Aletschhorn, Grünhorn and Finsteraarhorn in the Oberland; and in the Vallee Bishorn there’s Breithorn.

If I’ve got the timing right we’ll get back to our skis just as any crust is softening; when the top 5cm has softened to good corn. If you’re looking for powder on a north-facing slope you’ve got all day, but more usually you’re aiming for spring conditions, which come into play progressively later in the day on east, south and west-facing slopes.

Often I end up waiting a bit for that perfect time when the top is just a little icy, so we’ll hit perfect conditions midway, followed by slightly softer than ideal snow lower down. While descending, I’ll be getting some more shots, and also getting excited about downloading all the images and seeing what the day reveals. There’s usually at least a full day of picture editing to do after a day like this, as I take between 1,000 and 2,000 images on an average big route.

I generally live under a constant avalanche of photos. In spring I came back from ski touring in Greenland with 10,000 images to edit. I enjoy the results of editing more than editing itself!

If I can, I’ll usually get someone else to drive home, so I can start writing up notes from the day, punctuated by excitedly remembering key moments and looking to see if I got those images.

Back home, I’ll immediately load the images into my computer. I’m always ravenous after a big trip, so I’ll whip up a tray of roast vegetables. I work (or play) seven days a week in winter. I try to be in bed early but often end up editing photos into the night and then get up early again to hit the next day again full force.