The Swiss Cheese Model: Decision making in the backcountry

When duff call follows duff call, serious trouble could be round the corner. Backcountry editor Martin Chester takes a look at how to make the right decision at every layer

When duff call follows duff call, serious trouble could be round the corner. Backcountry editor Martin Chester takes a look at how to make the right decision at every layerAccidents will happen – especially in a sport that involves risky situations. Over the years I’ve been unfortunate enough to investigate numerous avalanche events and accidents. While some were just that – an unfortunate and unforeseeable coincidence of events – others were far more predictable. Wind the clock back and you can see a trail of small errors that led to a catastrophic finale.

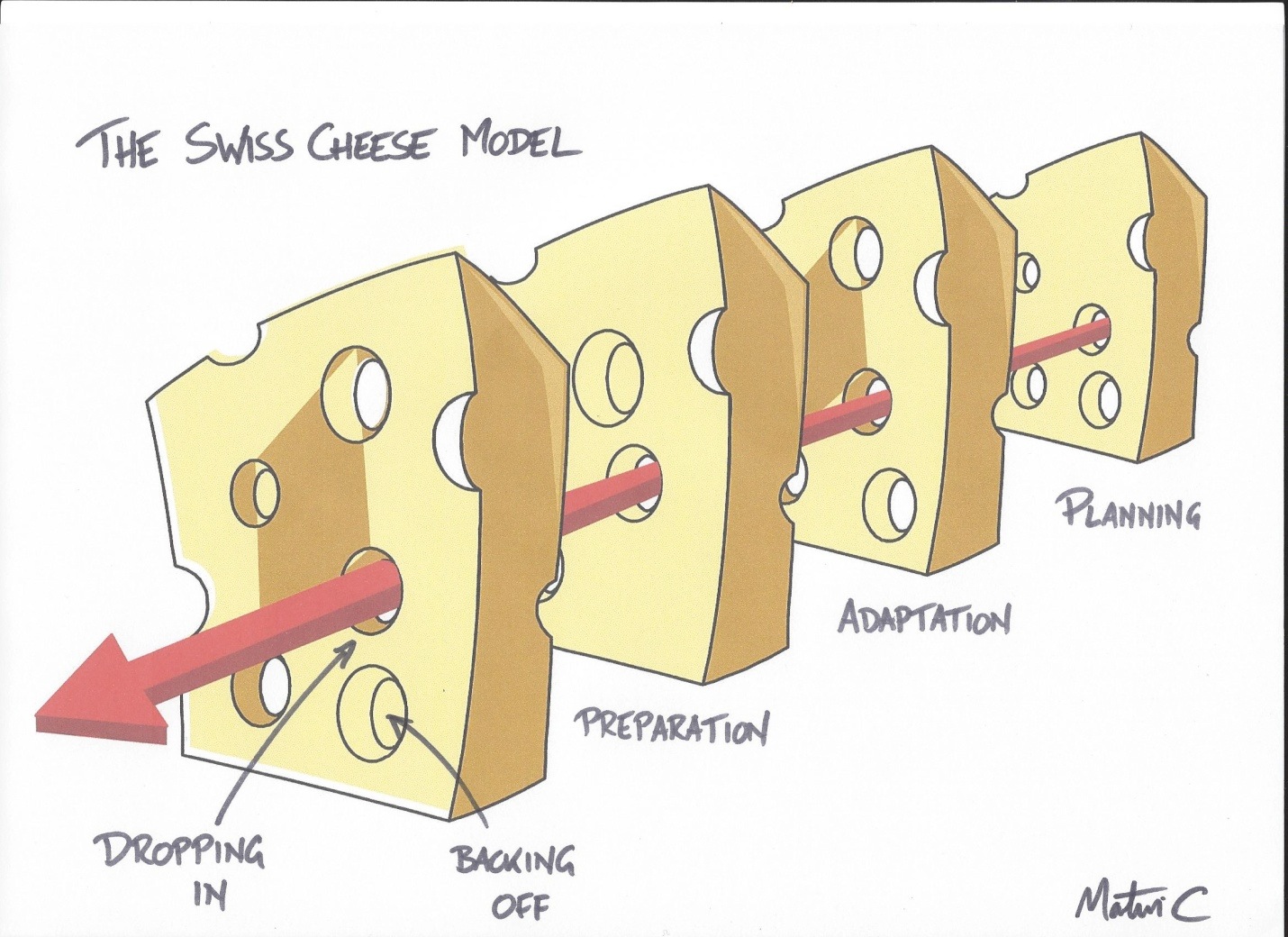

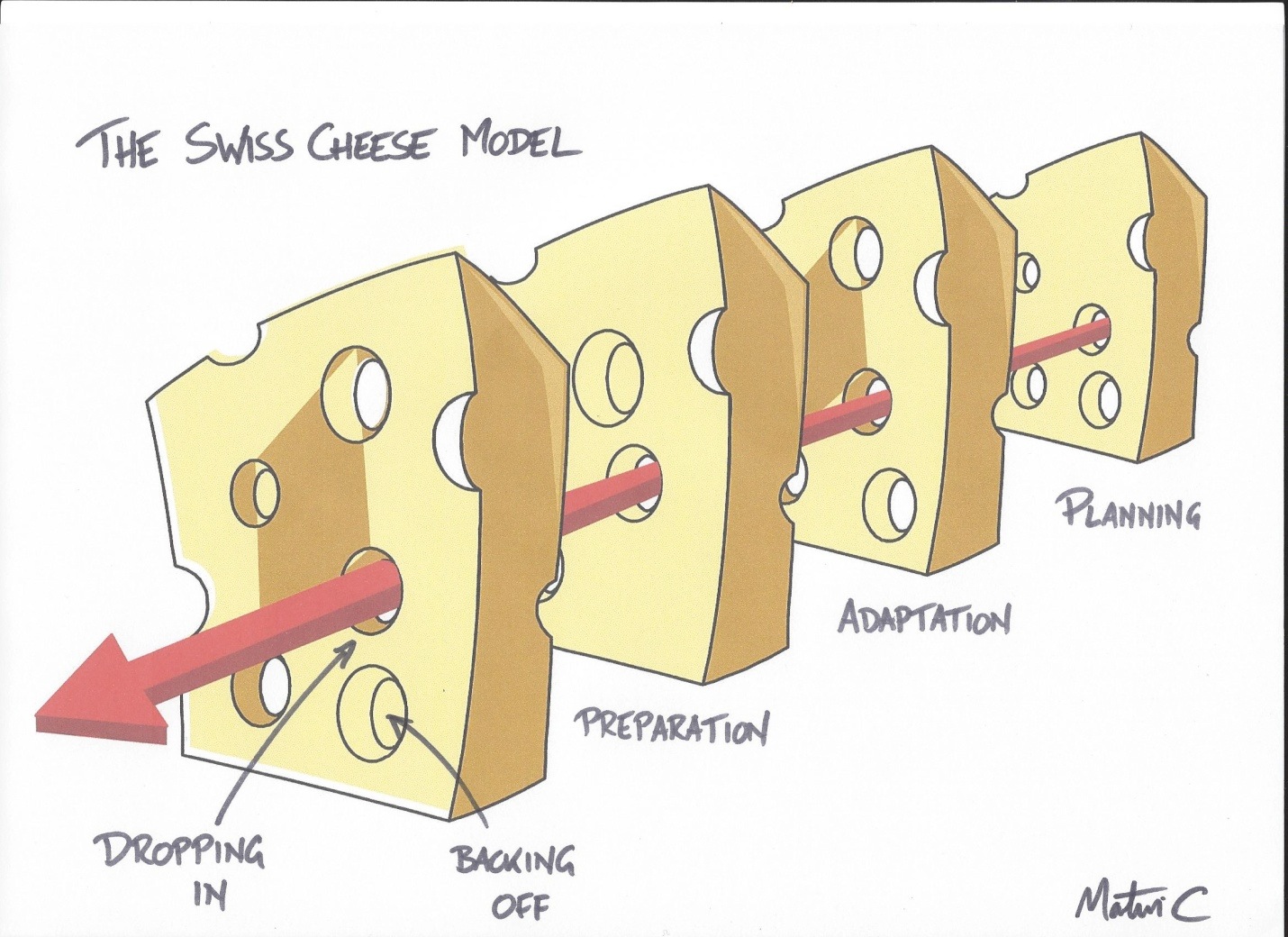

So how can we spot this trail before the dye is cast? This is where the Swiss Cheese Model comes in to play. The model suggests there are a number of layers of decision-making; and a number of types of decisions to make on each journey. Most of the time, we may make the odd duff call, and a risky choice makes it through. But if our plans and actions reveal a hole in each layer – and those holes align – then our decisions can lead to catastrophe.

Aviation offers many parallels; it’s an activity where decision-making keeps us safe. If we borrow their research we can learn a lot about decision-making at each layer of the cheese.

The first lesson is to be an agent of your own destiny – not a passenger – and this starts at the planning stage. The aviation industry has long recognised resignation as the first of five risky attitudes, where pilots think, “What’s the use?” and attribute disasters to bad luck.

Survivors have a plan. A realistic one. It is easy, in the enthusiasm of the night before, clouded by beer and boosted by a team psyche, for your ego to write cheques that your skiing skills will later struggle to cash. Don’t sit back thinking, “What’s the use?” and let others make a plan that threatens your enjoyment of your trip, if not your existence. What’s your plan, and how will you keep safe when committed to something you can’t handle?

Planning is based on historical information. Yesterday’s forecast, yesterday’s experience of snow, yesterday’s beta gleaned off mates in the bar. In the morning things may have changed – so plans needs to be reviewed or re-written. The fools that stick to Plan A regardless are handing over their destiny to fate.

Aviation has identified a common trap for this: the macho “I can do it” attitude. I’ll call it “ego”, as it’s rarely reserved for males alone – and often a case of people seeing failure to deliver a plan as criticism of their ego – rather than sensible hazard avoidance. It’s easy to think the good guys must be hard as nails and taking massive risks. The truth is they’re way more experienced, and very good at judging the perfect conditions. The secret is to have an equally appealing alternative plan (or several). This way you can change the game and still be seen as the saviour of the day, rather than the one who calls bullshit to the dream descent.

Here’s the big one that will have you raising your hand and claiming “guilty”. This is all about preparation – getting tooled up and taking it seriously. Do you wear a transceiver, do you switch it on, and do you know how to use it? How often have you not bothered to do a transceiver check? Be honest now…

Aviation puts this down to invulnerability; the idea that accidents happen to others. I’m amazed how often people (especially those who should know better) fall foul of this. I’ve skied with people who’ve spent a fortune on avi gear but when it comes to the crunch, the swanky toy is switched off. Hello people! You don’t get a chance to ask the avalanche if it would mind terribly if you just popped your transceiver on before you get engulfed…

So we’ve made it to the top. This could be the best ride of your life, or the last mistake you ever make. Let’s get this bit right, eh? Don’t fall into the impulsivity category: in aviation this is when people “do not think about what they are about to do; they do not select the best alternative and they do the first thing that comes to mind”. Sit back, consider your options and reassess: don’t just drop in!

He who runs away will live to fight another day. I didn’t get to be the mountain guide I am today without skiing cool stuff and climbing a bunch of north faces. But the things that taught me all I’ve learned have been those I didn’t do. I’ve spent 20 years not climbing the north face of the Eiger, however much I want to. I’ve even put the rope on at the bottom a couple of times; I just haven’t been there in the right conditions, yet. But those other big routes more than make up for it. The same is true for skiing. Sometimes you have to know when to back off. When the avalanche warnings are glaring red, don’t fall into the anti-authority “don’t tell me what to do” trap.

So now for the most important question of the lot. One day you’ll be at the top of the pitch that will slide if you ski it: how will you recognise that, and how will you be sure you’re going to pull the plug?

This is the final layer in the Swiss Cheese – and the ultimate chance to stop a catalogue of minor decisions leading to a catastrophe. Don’t leave a hole in this one. FL

adrotate group=”4″